Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing visualizes the racism of urban America as an unbearably hot summer. Blistering heat aggravates the city’s residents, fueling fear and hatred between racial groups until the city explodes into violent conflict. No one sustains serious injury, but Lee ends on a cautionary note, depicting collateral damage to the city, its climate hotter than ever before. This is a powerful metaphor with two implications. Firstly, our environment has the power to turn possibilities into eventualities. Secondly, and more importantly, our thoughts and deeds cultivate our environment.

Three years ago, George Zimmerman, motivated by racial profiling, attacked and murdered innocent black teenager Trayvon Martin but was acquitted of all charges. Last summer, police brutality in Ferguson demonstrated our nation has failed again to transcend racial violence. Last week, the tragic, senseless, and utterly cruel deaths in Charleston prove that we have yet to outgrow a shameful tradition of oppression which seeps through our national history. Moreover, online evidence suggests Roof, the shooter, saw the Trayvon Martin case as inspiration for his killing spree. Statements made during the Charleston court hearing will ring across the country with implications for racial relations–for better or worse.

Judge James Gosnell, Jr., originally selected to preside over this hearing, has been removed. Before his dismissal, he made the controversial claim that while the targets of the Charleston shooting are certainly victims, Roof’s own family are victims as well. Read more broadly, Gosnell implies that racial violence’s true victim is not just the target, but society at large. After all, we are “one nation–under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” Hate crimes transgress the parameters of ordinary crime and threaten to destabilize our country’s very ethical foundations.

The ideals of plurality and tolerance predate the United States’ desire for independence. Pilgrim settlers populated the North East coast to escape religious persecution in their homeland of England. When British expansionism threatened to constrict the colonists’ autonomy years later, they rebelled. Contrary to the modern narrative of the Revolutionary War, however, only a select minority of political agitators demanded bona fide independence for all American colonies. Charged by the emancipatory, egalitarian political theory of John Locke, the founding fathers rallied for self determination, their modest numbers compensated for by fervent idealism.

The colonist majority maintained an indifferent front of inertia towards the revolutionary movement, aligning with America’s other legacy: hierarchical social order. Cotton and tobacco farms, integral to many colonies’ economic systems, yielded maximum prosperity to their owners when fueled by slave labor. Universal liberation threatened their success. Thus, from its inception, our nation has developed a two-sided legacy of social organization: hierarchical society and egalitarian society. While landed aristocrats of the South supported the status quo hierarchical society, the progressive movements throughout American history have propagated egalitarian politics.

This polar opposition is, however, a simplification which omits troublesome nuances. The founding fathers aspired for a qualified egalitarianism–self determination–while maintaining the right to preserve social hierarchy. Equality in representation extended to land-owning white men and no further. Moreover, founding father and later United States President Thomas Jefferson not only owned slaves, but championed slavery-dependent agrarian economies and breeded slaves for the sole purpose of selling them.

Although its dominance retreated over the years, the fundamentally oppressive hierarchy dictated by slavery persisted for most of the following century in American history. The regime of slavery dehumanized the individual slave, rendering their political and human rights non-existant. The law designated a slave as property instead of a person, permitting inhuman treatment of a slave by his or her owner. Slaves recognized the schism between Constitutional ideality and plantation reality.

Nat Turner and others instigated slave rebellions, elevating hierarchical subjugation to violent social conflict between racial groups. Slave rebellions mark a political fissure in American history where the oppressed demanded equal status as their oppressors–much like the moments leading up to the Declaration of Independence. Moreover, such actions complicate our history and the very moral justifications for nationhood. Those that commit the atrocities of slave owners demonstrated our nation could hardly be considered a benevolent state, but rather a land of questionable morality at best and an amoral empire at worst.

The apotheosis of this internal tension was the Civil War; rather than mere conflict over the constitutional legitimacy of slavery, the Civil War was a battleground between hierarchical and egalitarian social systems. Although the Union won the Civil War, military victory alone could not erase a century-long legacy of racist sentiment grown under a plantation society. Americans never sufficiently questioned Confederate society’s moral essence, tacitly condoning the tradition to endure through an emerging Jim Crow regime which perpetuated social subjugation through segregation.

Civil Rights activists soon challenged the Jim Crow South’s regime of permissive bigotry; nevertheless, Supreme Court orders to bridge segregated communities, political efforts to aggressively prosecute lynch mobs, and activists’ vilification of racism met zealous resistance. Racial tension grew. Assassins targeted politicians on either side. Innocent blood continued to spill. Finally, augmented by the broadcasting capabilities of television, the Civil Rights effort gained momentum. Televised racial violence shocked the nation. Atrocities of the Jim Crow South could no longer be ignored. Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X heralded equality and social reform. The United States further exhumed its roots of oppression.

Two-and-a-half centuries since an idealistic minority rebelled and declared themselves the United States of America, we, the people, have attempted to cement a legacy of liberty. But, a legacy of inequality persists through structural racism. Intrinsically tyrannical and undemocratic, racism undermines the many positive ideals upon which our nation was founded. If history teaches us that a political movement’s number of supporters is secondary to how fervently its supporters believe in their ideals, what does it mean if a small yet persistent group of our population is actively racist in practice and in sentiment? Contemporary racism is a perverse reversal of years of political reform.

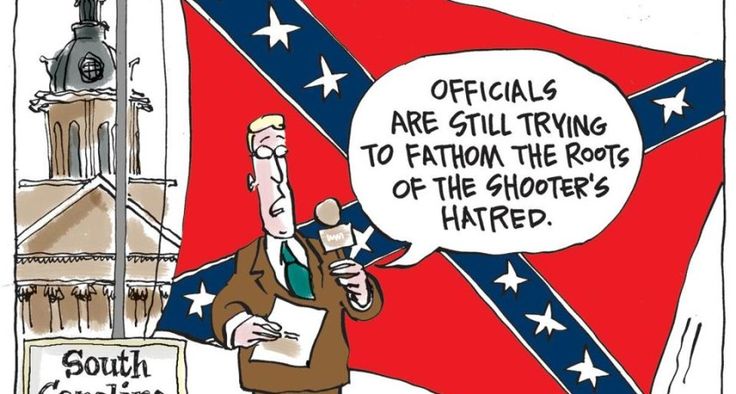

The hate crime in Charleston bears political resonance, potentiated by preceding acts of bigotry and hatred. The culprit is a Confederate culture allowed to persist despite knowledge of the history it represents. We are not, as Judge James Gosnell, Jr., claims, victims of racism. We are perpetrators, allowing our country’s climate to fester with the poison of hatred, fermenting it with our silence, fertilizing it with our apathy.

Martin Luther King, Jr., contended that indifference begets evil, as it is a permissive act. A farmer may not have ordered locusts to attack his crop, but his inaction still results in destruction. He is not a victim of the locusts. He is guilty of apathy. The Charleston massacre took place in a church during prayer. Its victims came together to promote peace and unity but were murdered in cold blood.