Science isn’t science without mistakes, which hopefully we learn from as we push forward in our respective fields. But just recently United States military and government labs made a rather egregious one. According to Reuters, a total of nine states and one United States air base in South Korea received shipments from the US military with live anthrax, a mistake that apparently stemmed from a CDC lab failing to effectively kill the bacteria before sending it to other labs not equipped to deal with live samples. Though the government asserts that the risk of something catastrophic happening are quite low, four people have been proactively treated for infection, though they have shown no signs of having contracted the disease. More horrifyingly, however, Reuters further reports that the U.S. army shipped these samples continuously over the period of a year.

Now, as I’ve already stated, the government making assurances that there is no risk of infection to the general public. Even those that could potentially have been infected are looking like they’ve dodged the bullet. Furthermore, the Defense Department and the CDC are launching an investigation to find out exactly how this happened, which is good–failing to properly kill an anthrax sample and then sending it to labs not equipped to deal with live samples is not a small mistake. As we learned from the 2001 anthrax attacks, codenamed Amerithrax by the FBI, this infection can be quite deadly. But what is anthrax, exactly? Let’s take a look at the science of this organism.

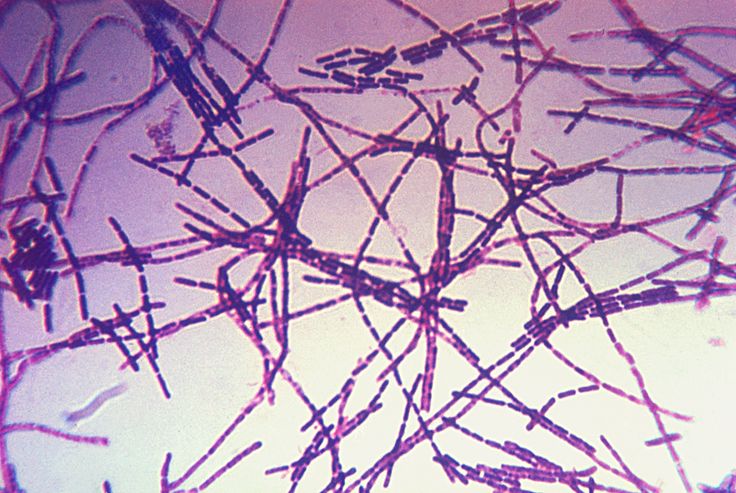

Anthrax is actually the name of the disease caused by a rod shaped, gram-positive, aerobic bacteria whose full scientific name is Bacillus anthracis. It is important to note that B. anthracis is a spore-bearing bacteria, a class of organisms that produce dormant structures called spores when resources are depleted or when they encounter an unfavorable environment to their survival. Though these bacteria do not normally reproduce via spores, these dormant structures can develop into full fledged bacteria. B. anthracis itself occurs naturally in the soil, and as such it is mostly grazing herbivores that are at the greatest risk of infection, while humans usually contract the disease through contact with infected animals. There are three main types of infection: cutaneous anthrax, which is an infection of the skin usually caused by some sort of cut or other injury; gastrointestinal anthrax, in which the host develops the disease after eating under-cooked meat from animals that are playing host to the bacteria; and finally inhalation anthrax, the rarest type, in which enough of the spores are inhaled to cause the disease to develop. Symptoms vary by infection type, ranging from lesions in cutaneous anthrax, to nausea, vomiting, fever, and bloody diarrhea in gastrointestinal anthrax, to flu-like symptoms, cyanosis, fever, and coma in inhalation anthrax. Death is a very present risk in both the gastrointestinal and the inahalation type of the disease.

Interestingly, though inhalation anthrax is the rarest form of the disease to contract naturally, it is how the bacteria have been weaponized. In fact, it is one of the best candidates for biological weapons, because it is so easy to grow and is so deadly. Dried spores in mass quantities are used for this purpose, dispersed into the air after being reduced to very small particles. Though a vaccine does exist, it is not easily obtainable, and the virulence of the bacteria is quite terrifying. The Amerithrax attacks killed five and sickened 17.

Now, from the way things look, it was not weaponized anthrax that was shipped to these laboratories. Rather, it was samples of live bacteria, which still present their own danger; researchers could still very easily have become infected and developed life-threatening symptoms. It is for this reason that the government is launching an exhaustive investigation of how this happened and also of our laboratories’ safety measures in general. This is for good reason. As we’ve made clear, the implications of this mistake are non-trivial. Let us hope that this is an issue that will be promptly fixed, and one that will not happen again.