The world wide web is in danger of being re-wired by corporate interests. Major Internet Service Providers (ISPs) such as Comcast and AT&T threaten to restructure the internet so that information exchange depends on how much the user can pay. Net neutrality is therefore not just an issue concerning fledgling entrepreneurs struggling to compete with large companies, but an issue concerning free speech: if the rate of information access depends on the size of the user’s bank account, then we have entered an era of pay-as-you go speech.

This is why, for the last several months, citizens have rallied for the FCC’s right to legislate net neutrality and regulate corporate influence over online communication. In the past few years, major broadband companies have waged a legal battle to relinquish the FCC’s right to regulate ISPs, and, in 2014, a federal court case ruled that regulation of ISPs fell outside the FCC’s scope of authority. In response, over 4 million people wrote to the FCC, while several others petitioned for direct federal intervention on the issue of net neutrality. While corporations and the public may dispute the need for government involvement, both parties agree Internet access is a fundamental source of empowerment. But is the Internet really neutral in the first place? And is open access to the Internet definitive of social progress?

As gangster Verbal Kint tells his prosecutor during an investigation in The Usual Suspects “The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.”

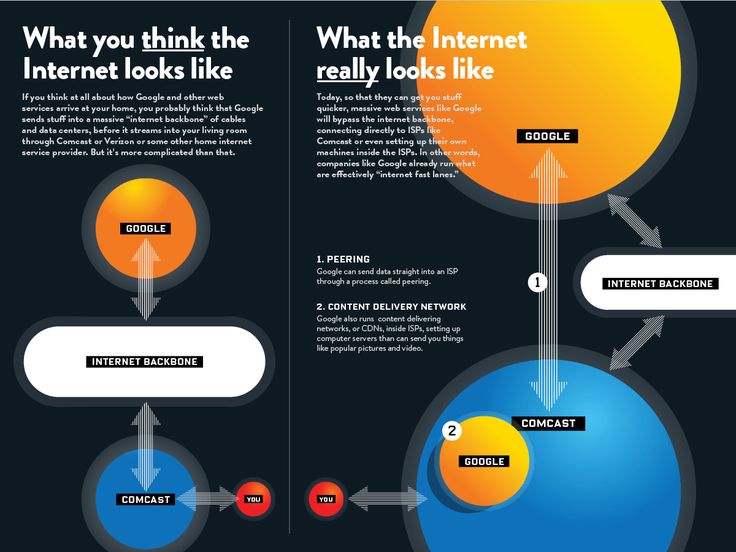

The net neutrality debate is mired in a web of misconceptions about how the Internet works. Most advocates on either side of the issue base their argument on a mental image of the internet that doesn’t line up with how the technology actually works.

Yes, it’s true that Internet service is a scarce resource which ISPs allocate across companies and individual consumers. But no, this reservoir of information isn’t the only road on the information super highway. In fact, major corporations like Google have the resources to build their own servers with direct connections to ISPs which act as a short-cut, bypassing all other Internet traffic. In effect, major corporations have already been paying for the internet fast-lanes which net neutrality supposedly prevents.

I think there’s a very clever reason for the heavily publicized corporate attacks on net neutrality–if a neutral internet is a myth, then net neutrality is a mirage distracting the public from the real issue at stake: corporate monopoly over the economy has seeped into corporate monopoly over Internet access, but the image of net neutrality presents a reversed depiction of this story. Disparity in Internet access is a symptom of a larger social problem of economic disparity

When asked whether he considered using his message to empower the public his artistic responsibility, John Lennon replied, “the people have the power. All we have to do is awaken the power in the people.” Public response to the negation of net neutrality in early 2014 proves Lennon’s statement. In 2014, the FCC lost the jurisdiction to regulate ISPs, all hope seems lost for net neutrality. A year later, the public’s voice cries out for change, and the government responds, signing a new net neutrality bill. Did lack of equal Internet access prevent the public’s voice from being heard? No. The public spoke, the government acted, and corporations lost despite their vast economic resources.

The public’s voice holds considerable economic and social force with or without access to the Internet. It’s a question of whether or not the public feels strongly enough to rally around a common cause. In the case of net neutrality, the public felt so strongly that its demand for government action sounded so loudly that action had to be taken. But when this energy is not directed toward issues which affect true social change, progress cannot be achieved.

Hence, net neutrality is a Trojan horse; it distracts public protest from the issue that should be contested: increasing size of corporations precipitating increasing disparities in economic opportunity. Moreover, the belief that technology access is the limiting factor in social progress is not a new strategy —cable lobbyists used the same rhetoric of technological determinism to loosen government regulation in the 70’s, and much of the rhetoric gets thrown around today when discussing Internet technology.

Technology is not a magic cure for social problems, it’s a tool created by people for people to use. Therefore, I caution against discourse which links access to technology with access to economic, social, or political privilege. Just because technology is a useful tool doesn’t mean it can change fundamental social inequalities. That’s on us, the people.